Kristen Holway, Senior Manager, Learning Practice

“We often don’t know much about the bad things that happen in childhood. We swim in violence as communities. However, many people in authority do not know about it. There’s a fundamental disconnect.”

So began Dr. Christopher Blodgett’s presentation to a group of philanthropic and public sector leaders about his recent report: No School Alone: How Community Risks and Assets Contribute to School and Youth Success. Blodgett, who heads Washington State University’s Area Health Education Center and CLEAR Trauma Center, was referencing our national dialogue on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs).

What the Data Tell Us

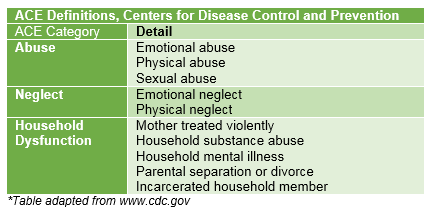

Findings from several hundred peer-reviewed research studies consistently support the role of ACEs as arguably the most powerful single predictor of health and well-being in adulthood. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “certain experiences are major risk factors for the leading causes of illness and death as well as poor quality of life in the United States.”

Even though research shows that “some of the worst health and social problems in our nation can arise as a consequence of adverse childhood experiences”[1], most of our national dialogue around ACEs has focused on adults reflecting back, according to Blodgett. There is limited data on the effect ACEs have on youth and childhood well-being. Blodgett and his partners at the Foundation for Healthy Generations have therefore been on a mission to unpack the influence ACEs have on children in Washington State. Their research explores the predictive but complicated nature of ACEs, opportunities for using trauma as a lens for education policy and the community assets and dynamics that support resilience.

Key Takeaways

Here are a few particularly powerful findings discussed during the May 21 workshop cohosted by Philanthropy Northwest and Foundation for Healthy Generations:

Academic performance suffers in communities with high numbers of ACEs. Twenty-eight percent of K-12 students in Washington State live in communities where more than 35 percent of the adults report high numbers of ACEs (three or more). As the percentage of high ACE adults in a community increases, fewer students in that community pass standardized tests. As the rate of community ACEs increases, so do the rates of suspension, severe attendance and school behavioral problems, and reported health problems among children and youth. This pattern is called the “ACE dose effect.”

Poverty does not cause ACEs. The data on the relationship between poverty and ACEs are complex and not linear. As poverty increases, the number of reported ACEs does not increase. And, while poverty is a more powerful individual predictor for academic achievement than ACEs, a high ACE-low poverty community looks like a high poverty community alone. This is one of the most ground-breaking elements of this research: the overall effect of ACEs on a child’s academic achievement and well-being cuts across income levels. This suggests that an anti-poverty strategy alone cannot solve school-level academic problems. Trauma interventions are distinct from poverty interventions and should be integrated into policy decisions. “Public policy focuses on disadvantage — we’re describing academic risk via ACEs and poverty,” said Blodgett. Reacting to this finding, one participant commented, “Poverty is relevant to ACEs because it steals resources and choice. It has an accelerant effect, even if it doesn’t have a causal effect.”

Community capacity matters. Communities with high capacity, as defined by Laura Porter, senior director of the ACEs Learning Institute at Foundation for Healthy Generations, are "flourishing communities that produce safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments. (They have) regular ways to come together, a shared identity, networked social and inter-organizational processes characterized by learning, reciprocity and social bridging... (and) shared times and venues for critical reflection and decision making."

Many trauma or school interventions focus on program improvement or the overall transformation of a particular system and not the transformation of an entire community. Foundation for Healthy Generations, which conducted 70 key information interviews in nine communities to augment Blodgett’s quantitative research, found that “whole community transformation” and the “breadth of strategies” for coping with and addressing ACEs matter. “Strong communities align work across many disciplines and sectors,” said Porter. “They intentionally use the whole system and have broad door to door engagement with resident leaders co-developing and implementing strategies. There’s a difference in efficacy, compassion, optimism and hope in high capacity communities.”

High capacity communities have a different “state of being” and they are intentional about “acting upon the future they want for themselves – focusing on community ‘being’ and not just community ‘doing’.” Low capacity communities, by contrast, are characterized by an external orientation where resident contributions aren’t meaningfully integrated into the “range of possible actions.” They don’t mine community data or have active learning loops like high capacity communities.

This information is hard to process because it suggests that none of us are immune from ACEs. Chances are, if you haven't had one ACE, that someone close to you has experienced "persistent, but unpredictable stress" as a child. “What’s interesting is that this is common to all of us, so (to some extent) it removes the blame from the conversation,” said Blodgett.

Actions You Can Take

The results of Dr. Blodgett's and Foundation for Healthy Generations’ research are important to you if you fund in education, health or human services. There are many paths to explore in this rich body of research, but three pieces of advice for foundations stuck with me:

- Schools can use trauma-informed care principles in student support systems and integrate them into overall learning strategies. Social-emotional competence of child is one of the most important predictors of education success and there are tested interventions such as Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (PBIS) that outline optimal levels of performance standards.

- Invest in infrastructure. Blodgett held up the Montana Office of Public Instruction as an excellent example of a public institution intentionally investing in mental health supports for kids and teachers.

- Sustain and coordinate community capacity building funding, such as investing in a neutral convener that helps the community synchronize multi-discipline and multi-sector solutions. Make sure that relevant data and research is available for residents and local leaders.

If you are interested in learning more about ACEs or Dr. Blodgett's research, please visit Foundation for Healthy Generations' ACEs Learning Institute.

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention