This is an abridged version of an article by Richard Kessler, dean, Mannes School of Music at The New School, originally published by the GIA Reader of Grantmakers in the Arts.

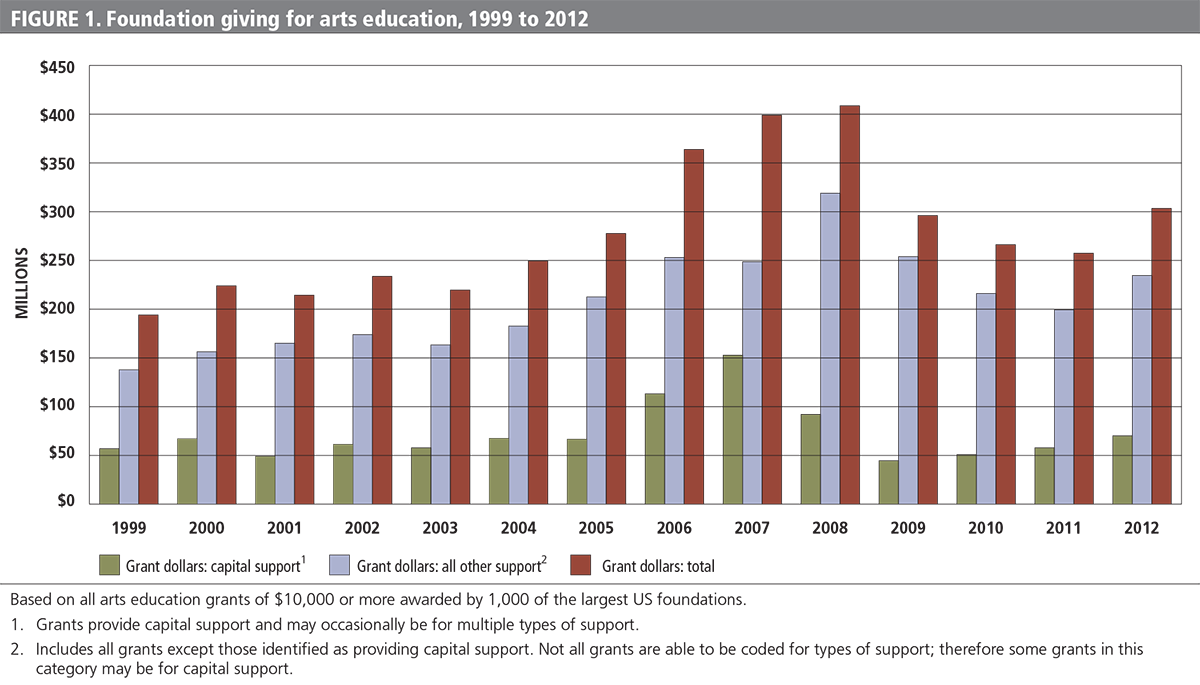

A new report, Foundation Funding for Arts Education: An Update on Foundation Trends, examines the Foundation Center’s data sets of grants of $10,000 or more awarded to organizations by one thousand of the largest U.S. foundations from 1999 to 2012. Key findings:

- Support for arts education grew by 57 percent between 1999 and 2012.

- Performing arts education benefited from roughly half of arts education giving.

- Arts organizations received three out of five arts education dollars and four out of five arts education grants.

- A majority of arts education grants targeted children and youth.

While funding for arts education has grown over the 13 years of data analyzed in the report, dollars peaked in 2008, with a substantial falloff correlated to the Great Recession. In the last year of data, 2012, we begin to see a recovery. In looking at size of grants (noncapital), across all years of data, the vast majority are under $25,000. The report looks forward to challenges to the field in terms of funding for arts education focusing primarily on the question of engaging the next generation of donors:

The contributions of arts education to a creative and prosperous society are well documented. But these learnings may need to be translated in a way that engages donors who want to be more hands on, see their priority as addressing specific populations, and may not immediately connect with how support for arts education can facilitate those goals.

What This Means: Arts Education Access and Equity

Information from the Arts and Cultural Production Satellite Account reveals that in 2012, 87.5 percent of arts education services provided in the United States came from government. When we place these data alongside the GIA report statistic that 4.4 percent of all funding goes to elementary and secondary schools, a picture emerges of the realm of funding for K–12 public school arts education, one that is primarily painted by the fractional amount that private funding brings to K–12 public school arts education. Consequently, funders need to think carefully about how their funding can leverage government dollars. Both strategy and tactics are critical in this regard. From the vantage point of equity, the economics of public schools dictate that programmatic funding can never result in all students receiving a quality arts education.

It is fascinating to consider the GIA report’s definition for advocacy: research on the role and effectiveness of arts education and advocacy to expand and enhance its influence.

Let’s take a moment to expand the world of advocacy and policy beyond this statement. Generally, the components of this work include the following:

- organizing: build power at the base

- educate legislators: provide information on issues

- educating the public about the legislative process

- research

- organizing a rally: mobilize for your cause

- regulatory efforts

- public education

- nonpartisan voter education: inform the electorate on the issues

- nonpartisan voter mobilization

- educational conferences

- training

- litigation

- lobbying: advocate for or against specific legislation. All nonprofits are permitted to lobby. 501(c)(3) public charities can engage in a generous but limited amount of lobbying.

Let’s now build out further by looking at two calls to the funding field. The first is recommendations to funders in 2010 by the National Committee for Responsible Philanthropy (NCRP):

In 2009, NCRP challenged grantmakers to provide at least 50 percent of their grant dollars to benefit marginalized groups and to provide at least 25 percent of their grant dollars for “advocacy, organizing and civic engagement to promote equity, opportunity and justice.”

Those two benchmarks provide a foundational touchstone for this new report. New analyses of education grant data suggests that of 672 foundations included in the sample, only 11 percent devoted at least half of their education grant dollars to marginalized communities and only 2 percent devoted at least one-quarter of their education grant dollars for systemic change and social justice. This suggests that many foundations seeking to improve education may not be as strategic in their grantmaking as they intend.

The second call is by Gara LaMarche, former head of Atlantic Philanthropies:

Funding advocacy and advocates is the most direct route to supporting enduring social change for the poor, the disenfranchised and the most vulnerable among us, including the youngest and oldest in our communities.

On the GIA website is a terrific series of white papers from organizations involved in systemic change. A lot of great work is going on, and I think it is important to note some fundamental areas that continue to evolve and grow:

- continued evolution of the teaching artist

- divergent organizational models/approaches coupled with better field-wide communications and support

- exemplary partnerships with districts (particularly midsized and smaller districts)

- citywide and region-wide coordination

- blending of in-school, out-of-school time, and community-based arts education

- better preservice training and professional development

- enduring models: some have weathered the vicissitudes of change (turnover of elected officials, economic downturns, educational policy churn, district leadership musical chairs, 50 percent of new teachers resigning by fifth year, etc.)

- bridges to important areas of multidisciplinary learning (STEAM)

- new national standards

- evolving assessment practice and better longitudinal research

- growth in parent and family programs/partnerships

- better data gathering and potential to take advantage of the world of big data

With all of this impressive growth and evolution, I believe that just as the GIA report understates advocacy and policy in its definition of arts education, it is clear from the report overall that advocacy and policy are lagging well behind. But if programmatic work cannot achieve equitable access to quality arts education, then the challenge to the field is substantial.

Speaking from experience, I see a tendency among arts education colleagues to overstate their work in advocacy and policy. There is lots of soft stuff going on, such as the sharing of Americans for the Arts policy pieces and one-day trips for “lobbying day.” But the real work of advocacy and policy is a long way off, partly due to the reluctance of funders to embrace the NCRP recommendations or LaMarche’s missive about the importance of this work. Some of the reasons why this area has been slow to emerge have to do with concerns around concrete results, confusion around what is allowed by law, and a general fear of conflict.

Two Examples of Advocacy Success

Let’s now take a quick look at two examples of successful work in advocacy and policy — the real deal stuff — and why this work should be further developed, supported, and ultimately embraced as we have all the other areas of practice.

The first is the California Alliance for Arts Education (CAAE), led by Joe Landon, executive director. They have four staff members, and according to their 2012 federal Form 990, they had total revenues of $532,192.

By any measure, this is a small organization, except when it comes to return on investment. Here, by creating organizational agency in policy research, government affairs, constituency building, and much more, CAAE was able to open up arts education funding in California to $1.6 billion in annual Title I funding. Their direct and well-documented efforts led to clarification on use of Title I funding (“Improving the Academic Achievement of the Disadvantaged”).

The math is not hard (really!). Four staff and $532,192 in annual funding open up $1.6 billion of annual funding to the neediest of K–12 public school students. The success is not by accident. It is through commitment to developing expertise and practice, even on a surprisingly small budget. What might be possible here if CAAE were adequately funded?

The second star in the return-on-investment orbit is The Center for Arts Education (CAE). Once the largest private funder of arts education in New York City, providing support, coordination, training, and more to what at one time were 130 schools partnered with over four hundred cultural providers, higher education, and community-based organizations, CAE has evolved its work into the rare hybrid of advocacy/policy and programs. (Without the programmatic work, there would likely not be enough funding to sustain the organization.)

According to CAE’s federal Form 990, in 2012 they had a total staff of 15, total revenues of $1,957,375, and total expenses allocated to advocacy of $356,528.

So, for $356,528 in advocacy expenses, what has been the return on investment for CAE? In 2013 their sustained efforts in lobbying, policy research, coalition building, media relations, and more led to $92 million in new direct funding for arts education in the New York City Public Schools. Uniting the mayor and city council around this issue saw $23 million base-lined in the New York City budget for four years.

My Call to Action

This work does not happen overnight. It requires new skills and a new view on how we evaluate success, and sometimes it puts organizations and the people associated with them into conflict, because when it comes down to it, they stand for something.

So in the end, my reflection is that when it comes to K–12 arts education equity, we are unlikely to get there in any sustained and significant way unless we as a field come to terms with the holistic maturing of our work through the support and development of serious capacities in advocacy and policy. And let us not forget that the equity issue remains one of inner-city public schools students getting the short end of the stick. These students are largely of color, economically disadvantaged, and heavily reliant on their schools for a sound and basic education because their parents cannot afford private lessons, special programs, and other arts experiences that come at a cost that can be dear. To get to every child, every school, we will have to move to a broad approach that includes policy and advocacy, adequately funded and supported. If you want all kids to have what the arts offer, then think about how you can make this happen. If it is more kids rather than all, well, you can always stick with a purely programmatic approach.

The full version of this article is available on the Grantmakers in the Arts website.