The recent election cycle has reminded us that even though the United States is one nation, we have many different ideas on how to make our country better. As I've been sharing Cascadia Foodshed Financing Project’s recent market research over the past few months, I've had a similar realization: We can all read the same research yet come to different conclusions about how to grow our regional food economy.

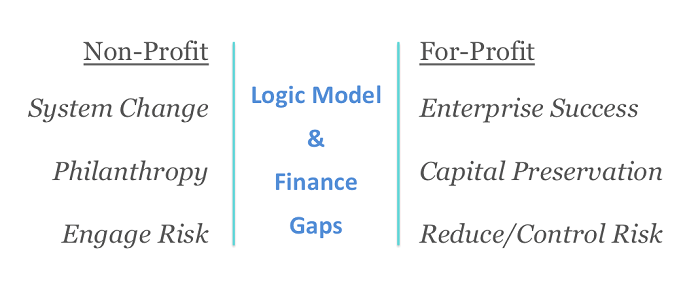

CFFP’s market research was commissioned to identify strategies that could catalyze growth of Washington and Oregon’s food economy. The research was reviewed by both a nonprofit program and a professional lender, soliciting their recommendations for where financing could help grow the viability of specific sustainable food products. Not surprisingly, the nonprofit and for-profit perspectives came up with different investment recommendations.

This divergence can be attributed to a logic model gap, or a difference in the tools used by different enterprises or departments to implement a shared goal. For instance, a foundation program department may seek opportunities to catalyze system transformation, while the same foundation’s finance department seeks to engage a specific enterprise or fund that yields a positive financial return through the growth and success of that specific entity.

In one of our foundation meetings, the program officers chuckled about this "obvious" issue: "You just described us over here [non-profit side] with our investment department over here [for-profit side].” Good! I'm glad we can shed light on the differences between the two sides of the same philanthropic coin. This is critical since both program and finance committees have been leaning in to impact investing opportunities. For CFFP, this makes us ask: Can we develop a fund, or similar investment vehicle, where grants and investments support each other? And how would that vehicle be structured?

CFFP’s working model is that a targeted investment vehicle, primarily for "impact first" investors such as foundations, can transform a system by investing in the viability of enterprises involved in the same supply chains. In other words, if a handful of investments in related businesses succeed, we will have transformed the system. We should not spend our resources just raising money to create a fund; we should spend time engaging to ensure the success of specific entrepreneurs and enterprises.

This leads to the second purpose of recent meetings and presentations: to "ground truth" the research and understand if the conclusions touch on real investment opportunities. This is a critical issue, for those concerned that there are not enough actual investments to warrant creation of a dedicated fund.

The Best Way to Find Impact Investments

The early signs are that there are actual investments — like assistance to transition to organic production, processing and other infrastructure — and working capital. (In particular, there appears to be a need for grain silos to separately store the rotational grains analyzed in our research.) Different investors have confirmed that the best way to find investments is to make an actual investment. This activity garners attention and respect for that investor, and other enterprises reveal themselves with similar needs. This is especially true if you are focusing on specific supply chains of business moving a product from field to fork.

For example, I was asked to discuss CFFP's market research at the recent Cascadia Grains Conference. After my presentation, I spoke with Mike Moran of Shepherd’s Grain, a company interviewed for the research. I asked Mike what he thought of the presentation (“right in line”) and mentioned that I heard they were seeking investment dollars. He said yes, but once they started moving on the idea for more milling they realized that their bottleneck was not milling but rather storage silos that separate their Identity Preserved grain from the normal commodity grain. Another participant chimed in saying his work in Idaho is yielding the same need, and that he is working to develop software that connects storage with trucking. From one rumor comes two investment opportunities, but only because of actual engagement with the entrepreneurs.

The commonality for us between these snippets is that working on the ground, in specific communities, is the best way to validate assumptions and identify true needs. We plan to continue to ground truth our research and seek investment opportunities, with the goal of organizing capital and interests towards our overarching strategy to grow the regional food economy. The hope is that we can identify partners and other investors who also see opportunity and need in this space.

Tim Crosby is project coordinator of Cascadia Foodshed Financing Project, a Philanthropy Northwest-sponsored collaboration of foundation and individual impact investors seeking to use market-based strateiges to grow the Northwest's regional food economy.