Kristen Holway, Senior Manager, Learning Practice

Less than a year ago, Washington experienced the largest wildfire in our state's history. The Carlton Complex Fire ripped through Okanogan County in north central Washington, burning a path of more than 400 square miles — an area roughly 4.5 times the size of Seattle. The blaze, caused by lightning strikes, and related mudslides destroyed more than 350 homes, businesses and farm structures; the estimated losses total nearly $30 million.

As we observe the first anniversary of this disaster on July 14, and as the Pacific Northwest's drought conditions greatly increase our risk for deadly wildfires this summer, I'm reminded of the interdependence of the people, government and funders in our region's disaster mitigation, preparedness, response, recovery and redevelopment.

The People. Many of the houses and buildings destroyed in the Carlton Complex Fire were uninsured, a common situation in remote rural areas, according to Carlene Anders, executive director of the Carlton Complex Long Term Recovery Group, a program fiscally sponsored by the Community Foundation of North Central Washington. The affected area lost more than a third of its housing supply, and rents have increased dramatically as a result — making it impossible for some residents to return, and for the region to fully prepare for future disasters. The fire also crippled residents who were once self-reliant by destroying their livelihoods.

The Government. The Federal Emergency Management Agency authorized the use of federal dollars to support 75 percent of the firefighting costs associated with the Carlton Complex Fire, including repairs to public utilities and schools. However, FEMA's authorization “did not provide assistance to individuals, homeowners or business owners and (did) not cover other infrastructure damage caused by the fire." Long-term recovery from a disaster demands ongoing case management and investment in everything from new housing to large farming infrastructure. FEMA is not authorized to support all the individual needs; local and state governments have limits, too.

The Funders. Organized philanthropy has an important role to play in resilience and long-term recovery from natural disasters, man-made accidents and humanitarian emergencies. Unfortunately, philanthropic support overwhelmingly places an “unmistakable emphasis on immediate relief,” according to a recent study by the Foundation Center and Center for Disaster Philanthropy. The 2012 study of 234 U.S. foundations found that 46 percent of the $111 million made in grants for disasters was allocated to relief, compared to 11.3 percent for reconstruction and long-term recovery, 9.9 percent for mitigation and four percent for preparedness. (The remaining support funded a mixture of approaches).While we would recommend having a disaster strategy that aligns with your foundation's mission and existing grantmaking strategies, we realize that it’s difficult to plan for what hasn’t happened. Long-term recovery and reconstruction funds are one viable and much-needed alternative to supporting community redevelopment and prioritization post-disaster.

Top right photo by Kristin Wall, Lifesong Photography; Center photo by Leslee Goodman, Carlton Complex Long Term Recovery Group

In Okanogan County, the Carlton Complex Long Term Recovery Group's fundraising work includes plans for rebuilding 40 houses for the area’s hardest-hit property owners, while government agencies focus on rebuilding affordable rental units.“Homes are basic," Anders said. "Without a place to live, families can’t get back on their feet.”

Building homes not only supports the residents and their neighbors, but also strengthens the region's tax base and supports its local timber, ranching and farming economies.

A community's resilience is inextricably tied to the resilience of the people living and working in that place, and its ability to prepare and recover from disaster. Needs also evolve over time as survivors realize the extent of their losses.

"Some losses, like homes and businesses, can take months, if not years, to rebuild, which is why long-term support is necessary," explained Leslee Goodman, the group's development and communications coordinator.

More Wildfires Expected This Summer

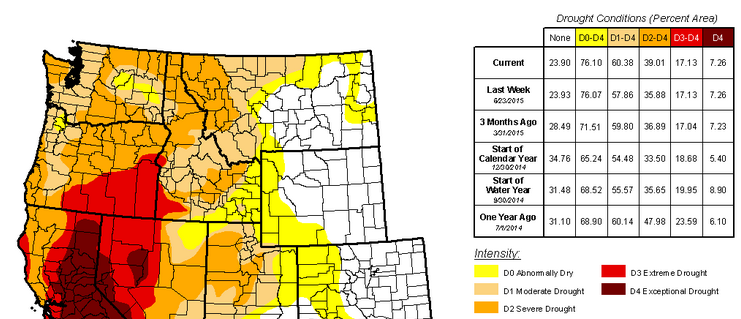

While many in the Pacific Northwest have cheered the recent hot, sunny weeks, the dry heat has made us even more vulnerable to another disaster like the Carlton Complex Fire — or worse. According to a Drought Monitor map released July 2 by the National Drought Mitigation Center, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, large sections of Idaho, Oregon and Washington are experiencing moderate to extreme drought; southeast Oregon is in "extreme drought."

"The National Interagency Fire Center in Boise ranked all of Washington and Oregon at above-normal threat for wildfires in July, along with northern and coastal California and western Montana and Idaho. By August, the threat should diminish some in Northern California, center officials say. The Pacific Northwest is not so lucky," writes Maria L. La Ganga, the newspaper's Seattle bureau chief.

Oregon has the largest wildfire of the region so far this season: a lightning-sparked fire raging on 26,000 acres near the Ochocho National Forest. In northern Idaho, the Cape Horn fire has charred more than 2,000 acres since breaking out on Sunday, Reuters reports.

Alaska's abnormally dry weather led to 300 wildfires in the month of June alone, prompting a disaster declaration for the Kenai Peninsula from Gov. Bill Walker. A recent report by Climate Central suggests Alaska is warming at a faster pace than the rest of the country; these “rising temperatures are expected to increased wildfire risks in Alaska” as well as lengthen the overall fire season (which has increased by 75 days since 1970).

Even in Washington's Queets rain forest, which typically receives more than 200 inches of rain annually, the Paradise Fire has now exceeded 1,200 acres, The Seattle Times reports.

And when it does finally rain again, the USDA reports that areas damaged by wildfire are at higher risk for flooding and mudslides, further complicating the ongoing needs of those communities.

"Fires destroy in moments what people have taken lifetimes to build," Goodman said. "It only makes sense that recovery, too, takes long-term investment and support."

Donors can contribute to the Sleepy Hollow Heights Fire Support Fund and the Carlton Complex Long Term Recovery Group Fund through the Community Foundation of North Central Washington.

To learn more about how philanthropy can contribute to disaster preparedness and response efforts in the Pacific Northwest, contact Kristen Holway.